Bunkers and shelters: stories of power and fear

/The latest generation of powerful are exploring alternative solutions to the natural habitat, financing projects to create artificial spaces far from the earth's surface. Some aim at hyperspace, others at underground shelters. However, if we needed to escape our world, is there any hope of leading a happy life underground? And how convenient can be investing so much money in these projects?

“Who wants to live forever... (when love must die)”, a song from the soundtrack for the 1986 film Highlander, reflects on the anguish of immortality and overcoming the death of loved ones. Even if it was possible to create a large place for a large community, we would face a long period of psychological and physical discomfort. Not only does love die, but beauty also fades. Who would, or rather, who could, live underground for a long time, without access to the light of the sky and an outside space, especially after experiencing how depressing an isolated life can be? Perplexity persists despite the awareness that the new survival shelters offer every comfort and present themselves as luxury homes. But luxury is not synonymous with beauty and, even if we can reproduce an environment similar to the natural one, how can we not fear the precariousness of a totally isolated and secret system?

SKYLIGHTS THAT OPEN ONTO VIRTUAL SKIES SIMULATE NATURE IN LUXURIOUS ATMOSPHERE

The market for bunkers homes has been growing in various parts of the world, and result attractive especially to the new emerging rich. In the US and the former USSR, old Cold War command centers and storage facilities have been transformed into survival condos and exclusive hangouts. More recently built secret villas are on sale in New Zealand, becoming topic of conversation among Hollywood stars and high-level athletes. But the claim to create independent and closed artificial systems always turns out to be utopian, and not only because freedom to move and explore distant and different places is what makes our planet the best place to live, but above all because the technology that promises safety and efficiency generates a persecutory mechanism among those who are excluded from it, starting from curiosity and ending to desire to invade.

The Gated Communities of the 70s are already demonstrating the failure of the defensive and closed attitude. The “security drift” fueled the desire of safety in the short term, guaranteed by the exclusivity of access to these protected places, but in the long term it made the outside less familiar and more threatening, requiring ever more courage and strength for facing everyday life. In the case of the bunker on the Hawaiian island of Kauai, the owner - guess who - tried to keep the project secret, imposing a ban on all workers, from architects to painters, from disclosing information about the structure, under penalty of dismissal. The construction site is protected by a 6 meter high wall, but the intention to maintain secrecy had the opposite effect: it stimulated curiosity for disclosure of details. Important information was revealed, such as the size of the surface (approximately 460 mq) and the cost of the operation (270 million dollars). The project is also rumored to include disc-shaped treehouses and vast cultivation fields, perhaps in the hope that natural or man-made emergencies will be short-lived, allowing people to enjoy open spaces as an alternative to the large underground home. The latter extends along a tunnel with over 30 rooms linking two opposite vertical connections to the surface containing offices, conference rooms and a professional kitchen. If this huge investment allows for an honest movement of money then we can welcome it, at least from an ethical and ecological point of view. The scale of intervention is relatively small, not very invasive as regards its ugliest part, and may have a future as evidence of yet another sad story of delirium of omnipotence and control, of fears and escapes.

The BOrbonic Tunnel of 1853

There are numerous testimonies of attempts to control contingent realities in the past, interesting not only from an architectural point of view, but above all for the clear and easy reading of certain social and political dynamics. The desire for change and the achievement of new economic, political and social balances have always generated tensions and therefore interventions in the territory by the powerful of the time. Two very well-known examples in Italy are "the Passetto di Borgo” conceived in 1227, and the more recent Borbon Tunnel built in 1853. The first, an elevated pedestrian passage approximately 800m long that connects the Vatican with Castel Sant'Angelo in Rome, had the purpose to allow the Pope to take refuge in adrian's mole in case of danger, while the second was created in Naples, designed by the architect Enrico Alvino, as a safe escape route for the Borbon monarchs, given the risks they had run during the uprisings of 1848. The well-sheltered place then became a refuge from bombing during the Second World War and was enriched with other objects of the time, becoming a major tourist attraction.

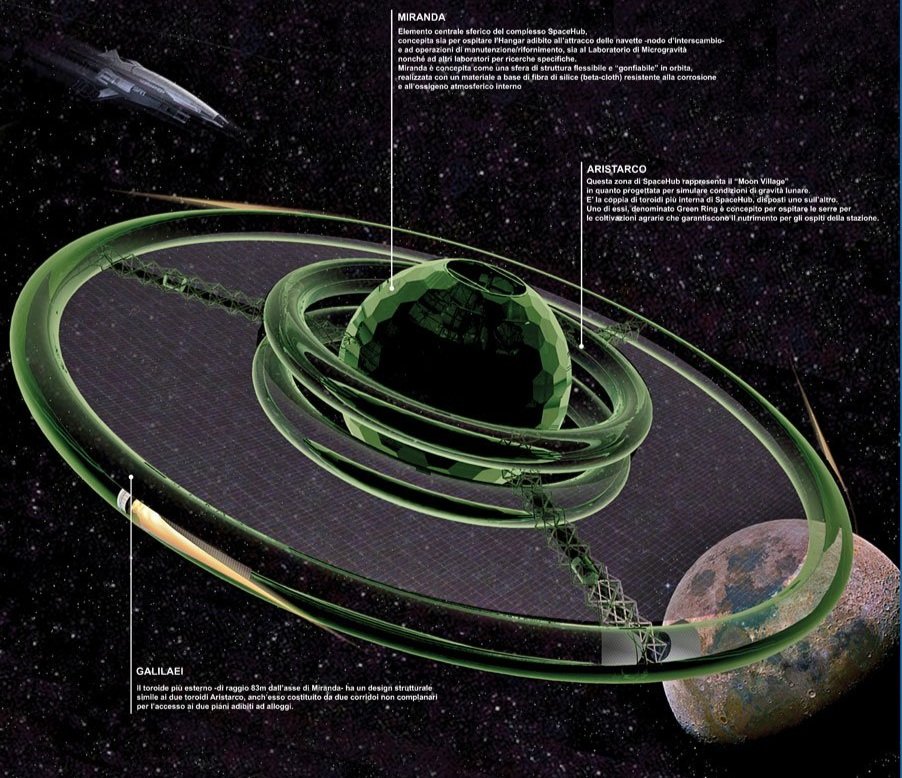

To attenuate the claustrophobic sensations these stories have just arisen, let's conclude with an all-Italian project from 2016, which aims at alternative life solutions in space (see photo below). The idea envisioned is for a cis-lunar city module with 1000 individuals located in different residential areas (neighborhoods) in orbit and on the Moon, in the hypothesis of an orbital interchange node with 100 people. The spaces are designed on principles of democracy and inclusion, trying, at least on paper, to minimize internal conflicts between the inhabitants, and abandoning the logic of selecting passengers, as has been done so far with astronauts. The anguish developed at the idea of underground bunkers is replaced here by a smile at the thought of a hyperspatial future. This solution doesn’t sound innovative at all, for the expectations fed by the last moon landing taking place over fifty years ago.

Anyway we hope the new generations will experience that not as an escape, but just as a new way of spending vacations.

2016 – ORBITECTURE, STAZIONE ORBITANTE, INFLATABLE SYSTEM, by PICA_CIAMARRA_ASSOCIATI